By Lena Zhu | Published by December 11, 2019

Kizito Kalima’s arms were tied behind his back — with a pistol to his head — as his Hutu captors led him to a slaughterhouse where all the other Tutsi villagers in Rwanda were. Then he laid eyes on a small red Nissan. The Hutu killers opened the trunk, threw his mother inside and drove off.

“They took my mom and she was killed and dumped into a mass grave,” Kalima said. “That was the last time I saw her.”

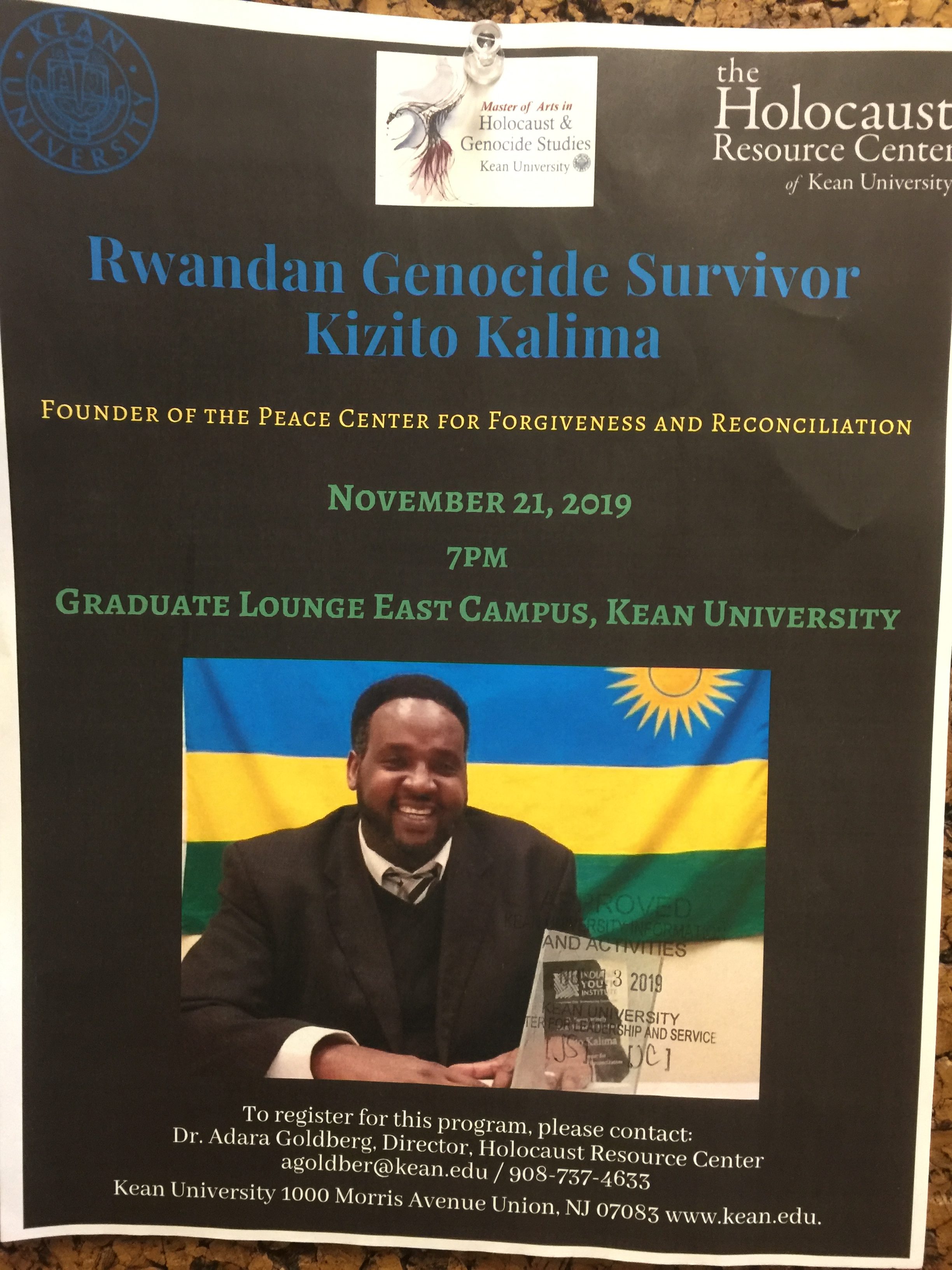

Kalima, the founder of the Peace Center for Forgiveness and Reconciliation, recounted his story as a fourteen-year-old boy trying to survive the Rwandan Genocide to a group in the Graduate Lounge at East Campus on Nov. 21.

The Peace Center for Forgiveness and Reconciliation, an organization Kalima founded, has the purpose to “come together and spread the message of forgiveness which leads to genuine reconciliation and long-lasting peace,” according to his website, ChooseToForgive.org. Their programs revolve around teaching youths the benefits of peace while working with mentors.

As the last born of his family, he remembered when the plane with the Hutu president was shot down, killing everyone on board.

“When we heard the news, of course, most of us who were oppressed were kinda excited,” Kalima said. “ I was excited, not because he had died, but because I felt like he was the cause of my suffering. I felt like, ‘Ok, no more curfews for all of us. No more oppression. We are going to live in peace!’”

However, his excitement was short-lived. When he told his mother the news, she told him “any time a leader of this country dies, we [Tutsi people] pay the price.”

He would learn that his mother was right a few days later on the back porch of his house. He heard a loud noise, then a banging, and then people jumping over the fence. He turned around to see where the noise originated and saw Hutus carrying an AK-47.

“I took off. I just ran. Jumped over the fence and ran across the street,” Kalima said. “When I was hiding, I saw my house burning. Everything was up in flames. My neighbors, anyone who was a Tutsi, or anyone who was against the government at that time, his or her house would be up in smoke.”

His neighborhood was completely destroyed. Kalima compared his neighborhood to that of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. His parents were gone. He didn’t know what to do. Ultimately, he decided he would be safer in his father’s friend’s house, whom he knew and grew up with since he was ten.

“I decided that I would leave my town and go to another place which was almost 20 miles away to the guy who my dad raised who grew up in the Hutu tribe,” said Kalima. “I reached his house at one in the morning. When I got there, I realized that he was happy to see me. He said, ‘Stay here and I will take care of you. I will protect you and see what’s going on’”

Unfortunately, word spread that Kalima, a Tutsi, was in his Hutu Brother’s home. They threatened to burn down the house with him inside because his Brother had refused to let him go. They decided to escape early the next morning when the river between his house and the next would be at low tide.

“Between my house and his house was this small river with a narrow bridge,” Kalima said. “This bridge was taken over by the killers. In the morning, we crossed the river, and a mob of 50 [Hutu] people got us.”

Kalima felt like he was going to die. They placed him in front of a mass grave. Getting ready, one of the Hutu killers swung the machete at his head. Kalima saw it and dodged as much as he could. The tip of the machete had scraped the side of his forehead and cracked his skull open. With blood gushing from his head, he passed out.

“When I woke up, I tried to move, but I couldn’t. I found out they have broken my ankles and taken my jacket,” Kalima said. “I only had a pair of jeans and a short-sleeved shirt. I decided to just go. While I was moving, I got caught.”

They took him to another butcher house the next day.

“We were lined up. Do you know how you’re lined up for your food when you go to the cafeteria? It was like that. Then you get chopped up. Something terrified me when I saw someone get chopped up with a chainsaw. And I was like ‘ok, I’m done. This is enough for me.’ I had a bloody face, a broken ankle, no shoes, cold, and I saw people get chopped off with a chainsaw.”

He decided to make a run for it. At this point, they were in his old neighborhood. He knew the back alleys and took off running. Eventually, he reached a church after having been denied sanctuary with his mother’s friend’s house. He stayed there for a couple of days until he heard a voice on a loudspeaker, telling him the war was over and for everyone to come out of hiding. It was the mayor, but it turned out to be a trick to lure the remaining Tutsis into a slaughterhouse.

Surrounded by the killers with machetes in their hands, Kalima decided to run and break away from them. Knowing his limited options, he wanted to die by a bullet wound — something quick and painless. Sure enough, as he and a few others ran up the hill, the Hutus started shooting.

“They shot a young kid to my left side. He dropped. The impact of the bullet was so powerful that I felt like I was shot. I fell down too,” Kalima said.

[Text Wrapping Break]Caught by killer dogs and brought back to the slaughterhouse, he saw the Hutus take his mother away and dumped into a mass grave.

This time, in the slaughterhouse, he was placed with other kids. He was the eldest and had to assume the leader position. Since the guards on the outside were “drunk, high, and falling asleep,” they all ran from the back entrance. Here, it was every man for himself.

Kalima ran into the swamps to hide out until the war was over. He hid in the swamp for almost three months before the rebels from the other side of the country were able to rescue him.

After being saved, reality sunk in. He had no place to go. No family to take care of him. He didn’t have anything at all. He moved around from foster place to foster place. He was angry and upset.

“I would sit outside, waiting for my parents to come. Because I was still in this big denial. I thought that my mom would show up somewhere,” Kalima said. “I knew that my mom was taken away.”

His only relief from his reality was basketball. He played in different countries and eventually, someone offered money for him to play in the United States. Kalima shook his head. He didn’t want the money. He wanted a place to stay and an education.

As a result, they moved him to Chicago. During high school, he had an ankle injury and was unable to play basketball. He graduated high school and went to the University of Indiana.

Kalima fell into a deep depression afterward. One day, he had a severe panic attack while driving. After having a talk with the nurse about sharing his genocide story to the world, he realized, after some hesitation, that retelling his story was a good way to manage his PTSD.

“I realized I was being held hostage by these people who killed my family, who raped my sisters, who almost chopped my head off…that was causing all of this anger and anxiety,” Kalima said.

Kalima knew that he had a good life in the United States and holding onto the anger of his past would only ruin that for him. So, he decided to let it go.

“I realized that everyone who became someone who changed the world has forgiven his or her abusers,” said Kalima.

His forgiveness did not happen overnight, however. It took about three years. The biggest change he had noticed was his migraines (from his PTSD and anxiety) had lessened from seven per week to three per week to none.

Nowadays, Kalima practices forgiveness and repeats a mantra.

“Every day I say, ‘I am going to be positive. I am not going to be angry. I am not going to be feared. No one can pull me down.’” said Kalima. “I define PTSD as People Trying to Slow me Down.”

His last piece of advice for the audience was, “You don’t have to be a super genius. You don’t have to be Superwoman or Superman. You don’t have to be incredibly wealthy to change the world. You just need to be a human being.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.